What is ‘Minnesota Nice,’ and how did a Converge church reach its multi-ethnic community by shedding the label?

Ben Greene

Pastor & writer

- Diversity

When Bitrus Bamai came to St. Paul, Minnesota, for graduate school, Minnesota Nice was waiting for him.

Bamai immediately recalls the day of his arrival — February 8, 2016. That’s when he first encountered this common trait of Minnesotans.

Bamai was quickly confused: people asked what he needed. But then, after he answered, there was no action. Bamai knew how to navigate this in his native Nigeria. But now, he was perplexed: When were Minnesotans being sincere?

It’s a question that has perplexed many newcomers to the state. So many, in fact, that, according to a 2019 Star Tribune article, the term “Minnesota Nice” was coined decades ago to explain “Minnesotans’ tendency to be polite and friendly, yet emotionally reserved; our penchant for self-deprecation and unwillingness to draw attention to ourselves; and, most controversially, our maddening habit of substituting passive-aggressiveness for direct confrontation.”

A year later, Bamai found some direction. He met two men at Community of Nations Church in Roseville, a suburb of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

“People have been honest” since that 2017 connection. “They mean it from their hearts when they ask what do you need? I was loved; I was cared for. They were concerned that I was here without my family.”

A struggling city, a sincere church

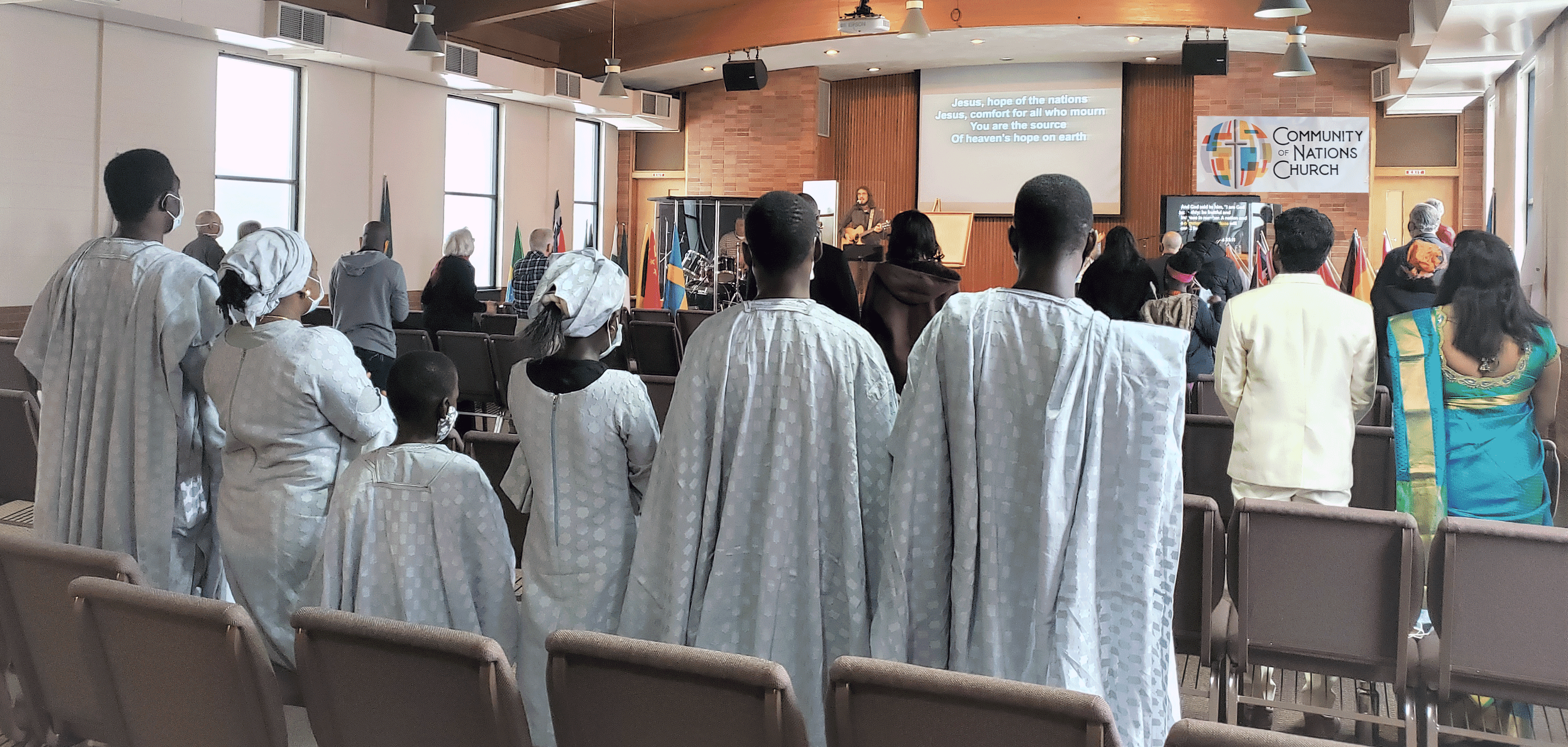

Bamai’s pastor, Kevin Walton, quickly acknowledges deep, formidable tension remains between cultures and races. Community of Nations Church is exactly 10.1 miles from the scene of George Floyd’s death. But God is forming something different in the people at Community of Nations Church.

For a few decades, the church has been pursuing multi-ethnic fellowship. Both now and in the past, Community of Nations has churches from other ethnic groups worshiping in their building. Other times, they analyzed their community to see how the church could become multi-ethnic.

Changing a church’s name during a pandemic

Their latest step was changing the church’s name in October, despite months of disruption tied to COVID-19.

Bethany Baptist Church started the formal name-changing process in 2019. The church members submitted possible names, 160 in all. Then the ongoing global pandemic arrived.

“Even through the COVID moment, it [the pandemic] never stopped the process because you could see the hand of God at work,” said Bamai, who is now a pastor alongside Walton.

In October, Minnesota officials allowed large in-person gatherings. Elders like Bruce Peterson and pastors Bamai and Walton wasted no time. The church quickly adjusted to in-person meetings instead of online-only services.

On October 25, the church had a celebratory service and announced the new name. Several members expressed why the new name was so valuable for them. Part of the service was a reading of Ephesians 3:14-21 by church members speaking in five different languages.

CNC Ephesians 3 Video from Community of Nations Church on Vimeo.

But in early November, Minnesota churches had to resume digital-only meetings. Community of Nations Church plans for their neighbors to hear about the church’s new name and learn about its decades-long desire for diversity sometime in 2021. The church hopes community members will see the church’s identity and future focus and will be drawn to become disciples of Christ.

Understanding Roseville’s history and the church’s identity

Peterson, who joined the Roseville church in 1985, grew up in this town, located on the edge of St. Paul. When he moved there as a young boy, the land north of his house was farmland. Cornfields surrounded his home.

Now, a four-lane highway has divided Roseville from the past and delivered the future.

“It’s changed a lot over the years, from a first-tier suburb to more of an urban area,” Peterson said. Moreover, what started out as young families moving from St. Paul is now an aging population that’s turning over.

“Most of us didn’t know what an African-American looked like,” Peterson said of his community in the 1960s.

Today, the number of students with a non-Anglo background equals that of Anglo students. Walton said school officials have told him that more than 50 percent of the students are non-Anglo.

This growth and shift in Roseville are reflected across the Twin Cities area. Three million people live in or near St. Paul and Minneapolis. And one million of those people were born outside America. This includes Hmong, Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian groups. People from Somalia, Nigeria and other nations on the African continent are also increasingly coming to the area.

Walton strengthened his service to the church by pursuing additional education: In his dissertation, he wrote the church needed to engage in the community and transition to a multi-ethnic church in leadership and practice.

But his desire, and the desire of the church, isn’t just to be diverse; they want to make disciples.

From janitorial volunteer to preacher, then pastor

As a student at Luther Seminary, Bamai was looking for a Baptist church. That was his church’s affiliation back in Nigeria. One day, he saw a sign for Bethany Baptist Church — the previous name for Community of Nations — not five minutes from his seminary.

He met two friendly men from Bethany one day. Then he called pastor Walton. After meeting together and sharing his story, Bamai was shocked when the pastor invited him to preach.

Bamai actually offered to use his janitorial skills to clean the church. But someone was already doing that. So, Walton capitalized on Bamai’s gifts and call.

“My first two weeks, I had a chance to preach,” he said. Bamai never saw that happen in Nigeria. A church should never give someone the invitation to preach so soon, he quips with warm laughter in his voice.

“Kevin just took interest in my story and had confidence.”

Why Community of Nations has a different future

Openness to what most churches usually don’t do has been in the work for decades, says Peterson.

“There’s been a group of people at Bethany that have had this vision for a long time,” said Peterson. “As things work out frequently, what we thought the schedule should be was not necessarily what God thought the schedule should be.”

There have been many tries since the 1970s and 1980s for greater diversity. Church members volunteered on the Red Lake reservation with indigenous people. And the church had a close partnership with an African American church in Roseville for several years.

The fruit of these new activities and relationships didn’t immediately change the church’s identity.

“There were a lot of bumps and mountains and valleys where changes were made,” Peterson said. “God intervened and dragged us along the path he wanted us to be taking.

“A lot of the time, this path was in agreement [with God’s will.] But there were also times when God said, ‘No, I’m closing the door on this. You’re not going that direction anymore.’”

One year, the pursuit of a more diverse fellowship created a painful sense of self-awareness. The church, Peterson said, realized their posture toward the whole community was more American than Christian.

"It was the first time as a church that we really admitted that we were wrong," he said. "Up until that time, it was the American culture kicking in. And we were saying, 'If you want to come to church here, you need to do church the way we do it.'

"All of a sudden, there was a realization that God was saying, 'That's not the way to do it,'" Peterson recalled. "It was a step toward where the church is now."

As Walton learned, the church often tried to include people of other ethnic groups without honoring their creative contributions to the church’s life. Members from the majority culture had genuine desire for change. But, Walton explains, they didn’t know how to let others fully shape the church’s culture.

The church’s vision, formed in 2001, says, “We will demonstrate the reconciling work of God by continuing to become an intercultural, multi-ethnic community of believers, reaching people for Jesus Christ, and together becoming his committed followers.”

“The church may desire to be a change-agent in the lives of others,” Walton wrote in his dissertation. “But she also needs to be changed by submitting to the Holy Spirit and entering dynamic relationships with others who bring other cultural perspectives and are participating in a creative change process.”

Walton believes his coming as pastor in 2015 is just one of the many steps the church is taking toward its vision statement. The desires he shares with the Roseville church encouraged him to end a 25-year ministry in Thailand.

“It was a big decision to come back,” he said. “But the one reason why I felt at peace to do that was their vision statement, who they were and what they were seeking to become. They had this large, clear commitment to grow as a more multi-ethnic and intercultural church,” he learned.

The process of changing the church’s identity

As the community around the church changed, the church first had to recognize the town’s demographics were diversifying.

“From way back, 20 years ago, they were starting down the path,” Walton said. “That was things God was doing in the late ’90s to change it from a predominantly white church.”

From there, they started rewriting their vision statement. Revelation’s message that the church is a people of every tribe, nation and tongue inspired them.

“That’s really the goal that I have seen for a long, long time, to bring many nations together to worship our Lord,” said Peterson.

Next, the building was redesigned with more space for people to be together in informal ways. Another major step was a new name and welcoming non-Anglo leaders.

“It’s one thing to invite an outside group [from another ethnicity] to rent your space,” Walton said. “It’s another thing to invite people of other cultures to be part of your church as a member.”

“It’s still another thing to invite people into leadership and submit yourselves to other forms of leadership, other forms of worship, other ways of solving problems.”

We are not large. But we have large hearts. There is room for everybody.

Originally, Bethany Baptist Church — like many Converge churches — was started by Swedish Baptists. Over time Bethany became a predominantly white suburban church. Now, Walton said Community of Nations is undergoing the transition to a multi-ethnic church.

“It’s been a long process,” Peterson said. “It started a long time ago.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever pulled taffy, but I’d compare it to that. If you pull it slow, it makes a beautiful product. But if you pull it fast, you just break it,” he said.

Bamai has experienced the change himself in the last three years.

“We are not large,” he said of the church’s size. “But we have large hearts. There is room for everybody.”

Before COVID-19, Walton said the church was averaging 80 to 100 people in Sunday services.

“The church is a diverse family in terms of generation, income and socioeconomics and diverse in terms of culture and our country of origin,” he noted. “We celebrate the richness of those differences.”

While a student at Bethel Seminary, Walton said many refugees came to the St. Paul area from Southeast Asia. That gave him a vision for cross-cultural friendships. He sponsored a family who eventually lived two miles from Community of Nations Church.

Walton left for Thailand not long after that family settled. When he came back 25 years later, someone in that same family became Walton’s Realtor. Generosity and love had come full circle: the family Walton sponsored was ready to help Walton’s family find a home.

Churches willing to take the long journey, willing to surrender to a God of unending love, are discovering a new culture and identity that’s far greater than their past. Such a journey offers more and more people from a multi-cultural world the chance to be disciples of Christ, not culture.

“We’ve not arrived yet,” Walton added. “Now we’re getting into some of the deeper issues. Working through those can help us find that fulfillment, that true community of a diversity of nations.”

Which means more and more people like Bamai will experience the great distance between God’s love and Minnesota Nice.

Changing a church’s identity

What can your church learn from Community of Nations’ journey to become a multi-ethnic church? There’s no manual. But some of these steps may fit your church:

- Look at your community. What’s staying the same? What’s changing? Ask the same questions of your church.

- Seek God’s input in prayer. How does the Head of the Church see your church?

- What is a different end goal or vision for your church? Write it down, talk with elders, your pastor and friends at church in a constructive way.

- For elders and leaders, begin to consider intermediate changes that lead to the new vision. Form a plan or path as best you can with the congregation’s help.

- Be open to who God brings to your church. Could they serve? Could they be in leadership?

- Expect a long journey; it took your church time to get where it is. Change will be slow.

Ben Greene, Pastor & writer

Ben Greene is a freelance writer and pastor currently living in Massachusetts. Along with his ministry experience, he has served as a full-time writer for the Associated Press and in the newspaper industry.

Additional articles by Ben Greene

.tmb-thumb115.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=3a5734f3_1)