Steve and Amanda Bialy were enjoying coffee in southwestern England nearly five years ago in a Methodist chapel repurposed as a pottery shop and cafe. They were on holiday when, just a few sips into his coffee, Steve saw part of a banner tucked in the cafe’s corner.

Most of the shop’s walls displayed pottery, handbags or other artisan crafts. The red and white banner, however, drew Steve’s focus as if the banner were more than a long-ignored relic.

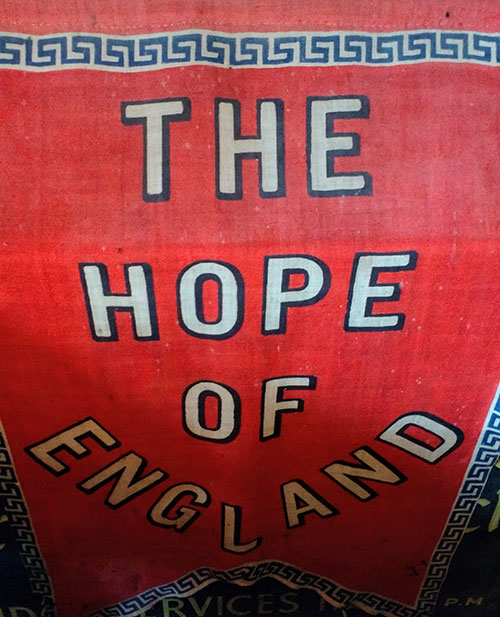

Across the banner were the words “The Hope of England.”

He called to his wife to take a look. Even after the church became a cafe, no one threw away the message of mercy.

Long forgotten, the surprise find of the banner formed a lens into England’s spiritual vitality. What the people around Bialy forgot became an unforgettable revelation of spiritual needs around him.

“They pushed the banner off to the side,” he said of the coffee shop decor. “Is the hope of Christ here? Is the hope of the gospel here? It was so clear it wasn’t. There are so many towns and villages across the U.K. where there’s no gospel-proclaiming churches.”

The U.K. and Ireland’s spiritual void stimulates the Bialys to shift their ministry

The Bialys lead the U.K. and Ireland Initiative. They came to London in 2019 after pastoring a Wisconsin church, but the pandemic forced them to stay online and closer to home in their ministry’s first two years.

But finally, Bialy said the ministry has an active year ahead. There are four emphases for the U.K. and Ireland Initiative: planting churches, revitalizing churches, training and equipping leaders and ministry to least reached or unreached people groups in the U.K. and Ireland.

“We are asking God for a thriving gospel witness to take root so people can meet, know and follow Jesus,” he said.

Related: Watch a video of the Bialys discussing their ministry in the U.K. and Ireland

So, Bialy is building relationships with church and ministry leaders in the U.K. and Ireland to see how Converge can contribute to what God is doing through these servants. He said Converge isn’t trying to take the lead.

Instead, the initiative seeks to position Converge as a supporting partner intent on overcoming obstacles to the gospel movement. Converge’s role could include sending global workers, generating financial engagement and helping train transformational leaders.

“The vision is for that to happen so that all these people living in communities where they have no access to the gospel will be the last generation to die without that being available to them,” he said.

‘A thing of the past’

The spiritual situation in the U.K. and Ireland is dire from a human perspective based on almost every indicator.

“The U.K. is thoroughly post-Christian,” Bialy explained. “Christianity is just considered a thing of the past.”

Trevor Archer pastored a British church for 25 years. Before that, he was a businessman following Christ since his teen years. The 74-year-old agrees with Bialy, who joined the church that Archer formerly pastored.

“I think Steve really gets hold of how different Britain is to America,” Archer said. “In America, people still respect and love the church. In Britain, people hate the church. That’s the difference.”

Bialy expanded upon how people receive and view Christianity. Many of his neighbors in London ― seen as the U.K.’s epicenter of evangelical Christianity ― view Christianity as something interesting, like a person’s hobby. People often view Christians as naive people in a rational world guided by science.

Why does Christianity get a different response now?

Archer, now the London director for the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches, observes the difference in spiritual responses to Billy Graham making two trips, decades apart.

In the 1950s, Graham traveled to the U.K. to hold an evangelistic crusade. Archer said the international evangelist could mention David or Daniel in sermons and Britons, even if they weren’t churchgoers, understood Graham’s message.

However, a few decades later, people no longer had familiarity with Christian narratives and characters. So, the benefits and blessings of Biblical teaching didn’t make the same impact as Graham’s 1950s ministry, Archer said.

Nowadays, people ministering in the U.K. and Ireland must start much further back in the Christian message. Like Paul in Athens, today’s Christian disciple-makers begin by talking about the creator of everyone.

“It is the difference between Acts 2 and Acts 17,” Archer said. “You have to start at Acts 17, with the knowledge that everyone is created in the image of God,” he explained. “People are so far back from the gospel. You can’t assume people understand anything about the Christian gospel.”

Bialy and Archer explained some reasons for this cultural trend away from Christian paradigms and understanding.

One reason people don’t worship is they see it as irrelevant. Over time, Bialy and Archer said, many churches in England shifted their teaching away from the gospel and Scripture to emphasize good deeds. Eventually, U.K. and Irish people concluded they could be good people without the church.

Another reason is people are suspicious of the church because of how ministers or high-profile Christian leaders have treated people.

Starting new churches is difficult not only because of these cultural reasons but also practical ones. Buildings and meeting spaces are scarce and costly. Plus, people in a community can have a strong sense of connection with the past. So, for example, a church built 900 years ago may be beloved, even if people no longer worship there.

The gospel is still incredibly attractive

Even with the challenges, Archer knows the gospel is still tremendously effective for life transformation. The key, he said, is presenting the gospel as it is without contaminating the gospel with culture.

“How can we remove these barriers to people hearing the gospel?” he asked. “There’s enough barrier in the gospel itself. The gospel in itself is incredibly attracting but also incredibly repelling when you find out you can’t please God. So how can we remove barriers like songs, buildings, how you use buildings and how you wear clothes?”

Related: Is your church ready to create an evangelistic culture?

There are many opportunities for Converge’s U.K. and Ireland Initiative.

First, the United Kingdom and Ireland are a crossroads of the world. Reaching people in the U.K. and Ireland can help transform people everywhere.

“There’s a strategic opportunity to reaching people here, particularly in the least-reached people groups,” Bialy explained. “They can go to places where Westerners never could and have an instant impact culturally that would take years for a Westerner to have.”

Related: Converge has a U.S. initiative to disciple people who can transform their homelands

Second, Converge has a growing network of partners offering internships that create a powerful context for learning and serving. For example, the U.K. and Ireland are near-culture places to the United States. Therefore, global workers can serve with less preparation, such as learning a language.

Still, internships generate cross-cultural interactions so God’s servants can learn and grow significantly. One of these partners, The Alliance for Transatlantic Theological Training or AT3, offers American believers an opportunity to serve meaningfully while also benefiting from the wisdom and experience of Christians in the U.K. and Ireland.

“There’s a cross-cultural dynamic but there’s so much you can benefit from it because it’s such a near-culture thing,” Bialy said. “You can really engage with culture in a very meaningful way.”

So, the short-term opportunities can equip Americans to serve more effectively in the U.S. as it becomes more post-Christian. But, at the same time, Americans can make significant contributions to ministry efforts in the U.K. and Ireland.

There is a historical precedent for churches in the U.K. and Ireland working with American leaders. Dwight L. Moody, an American preacher, and Charles Spurgeon, a London pastor, used their evangelism gifts and made disciples in both countries. Partnerships across the Atlantic Ocean go back to the Great Awakenings, great times of conversion and ministry in the 18th century.

“Between our cultures, good things happen when we cooperate around anything, especially in the church,” Bialy added.

Bialy has hope in God for both countries. Furthermore, his brothers’ and sisters’ strong faith and true hearts for Christ give him confidence.

He explained they have a genuine love for their community and emphasize collaboration in gospel ministry efforts.

“There’s a humility and dependence on the Lord, in the British church, that is compelling,” he said.

The puzzle of ministry has pieces coming together

For that reason, a banner about the forgotten hope of the U.K. and Ireland continues to motivate Steve and the team of people he serves alongside.

Churches regularly close and following Christ may seem naive or even despicable to many U.K. and Irish people. However, the churches on both sides of the Atlantic continue to support one another in the great commission.

For example, a Converge church in Boston knows people at the same church Bialy now attends in London. The American church wants to help start churches, strengthen churches and make disciples in the U.K. and Ireland.

“These are not pieces you can arrange,” Bialy said. “The Lord just puts them in front of you and helps you see what’s happening. Other opportunities are starting to emerge, ways in which the Lord is starting to open doors for partnership with Converge.”

Converge is asking God for a gospel movement among every least-reached people group – in our generation. Learn how we are playing a role in accomplishing the Great Commission and how you can be involved.